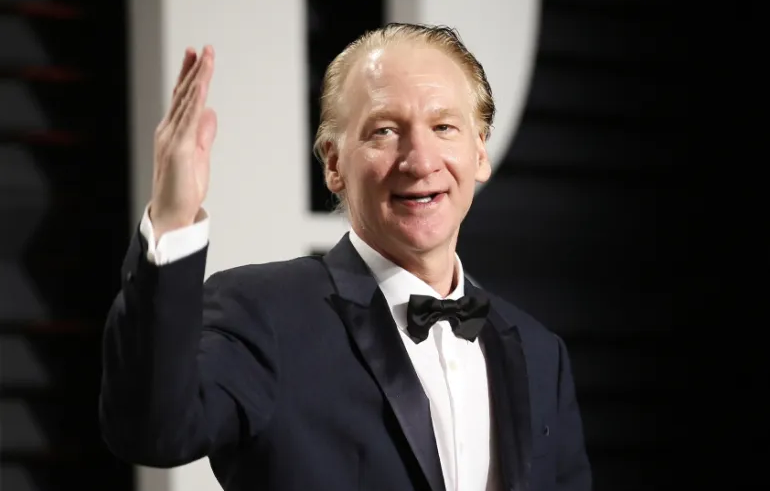

Bill Maher’s recent assertion that Christians in Nigeria are victims of a “genocide attempt” has ignited a wave of criticism for its oversimplification of a deeply complex crisis. On his show Real Time, Maher claimed that over 100,000 Christians have been killed and thousands of churches burned since 2009, painting a picture of systematic extermination. While it is undeniable that Christian communities in Nigeria have suffered brutal attacks, particularly from extremist groups such as Boko Haram, ISWAP, and various armed militias, experts caution that labeling this violence as genocide misrepresents the multifaceted nature of Nigeria’s insecurity and risks inflaming sectarian tensions.

The violence in Nigeria is not confined to one religious group. It stems from a volatile mix of ethnic rivalries, religious divisions, land disputes, and resource competition, all exacerbated by weak governance and economic hardship. Both Christian and Muslim communities have been targeted in attacks, and entire villages, regardless of faith, have been devastated by terrorism, banditry, and communal conflict. While the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Nigeria reports that at least 145 priests have been kidnapped and 11 killed since 2015, these tragic figures do not meet the legal threshold for genocide, which requires demonstrable intent to destroy a group in whole or in part.

Critics of Maher’s remarks argue that his narrative, built on unverified statistics and sweeping generalizations, distorts the reality on the ground and risks fueling divisive rhetoric. Gimba Kakanda, a senior aide to Nigeria’s vice president, emphasized that Maher’s portrayal ignores the country’s internal complexities and misuses data to push a sensationalist agenda. The timing of Maher’s comments, coinciding with Nigeria’s reaffirmation of support for a two-state solution in the Israel-Palestine conflict at the United Nations, has led some observers to question whether his statements were politically motivated rather than grounded in genuine concern for Nigerian Christians.

While the suffering of Christian communities in Nigeria is real and demands international attention, framing it as genocide oversimplifies the crisis and undermines efforts to address its root causes. Nigeria’s challenges require nuanced understanding and coordinated solutions that strengthen institutions, promote interfaith dialogue, and tackle socioeconomic disparities. Reducing a complex national tragedy to a single narrative risks obscuring the broader patterns of violence and the shared suffering of all Nigerians. In the pursuit of justice and peace, accuracy and context are not optional, they are essential.