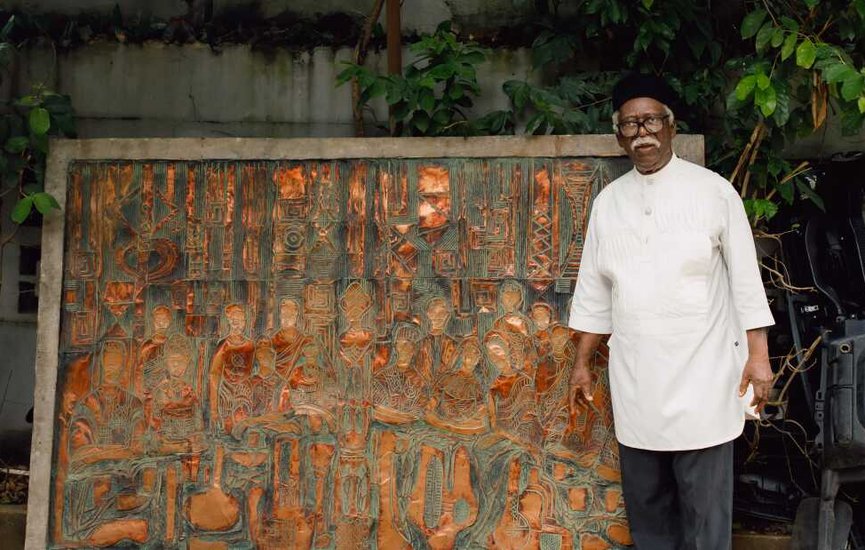

"This is one of the greatest things to have happened, not just to my art, but to Nigerian artwork," says 93-year-old painter and sculptor Bruce Onobrakpeya as he takes in the exhibits at Tate Modern, one of London's leading galleries.

"The collection is incredible, and it brings back memories from 50, 60, even 70 years ago," he adds.

Onobrakpeya is among over 50 artists whose works are featured in Nigerian Modernism, an ambitious exhibition at the gallery on the south bank of the Thames, showcasing Nigerian art from 1910 to the 1990s. For Onobrakpeya, affectionately known as Baba Bruce within art circles, Nigerian Modernism represents "a transfer of old ideas, materials, technologies, and thoughts into a modern context."

"It’s about projecting the present while showing the path to the future," he explains.

As visitors walk through Tate Modern’s expansive rooms, they encounter works that blend traditional Nigerian techniques, like bronze casting, mural painting, and wood carving, with European influences. The exhibition features both realistic paintings capturing historical events and more abstract pieces, including works by visual artist, drummer, and actor Muraina Oyelami.

Oyelami is honored to be part of such a major exhibition, though he’s indifferent to being labeled a "modernist."

"I created art, paintings. If critics want to call it 'modernism' or whatever term they choose, that’s their perspective," he says. "If that’s what they call it, why not? I don’t mind."

For Oyelami, the 1960s and 70s were an exciting yet turbulent time for Nigerian artists. The Tate’s collection traces the country’s evolution from a British colony to an independent nation, all while navigating the horrors of a devastating civil war.

The Biafran War (1967-1970) is reflected in the works of artists from the Nsukka Art School, a significant movement founded by students and professors at the University of Nigeria. It’s one of several influential art collectives highlighted in the exhibition.

“It’s not just about individual artistic practices; it’s clear that many of the artists in this exhibition were guided by a sense of collectivity,” says Osei Bonsu, the exhibition’s curator.

Bonsu has curated a diverse range of works—spanning from watercolors to photography, intricate thorn carvings to political cartoons. Artists from various Nigerian ethnic groups and the country’s large diaspora are represented. Despite their differences, all of them, according to Bonsu, share "radical visions of what modern art could be."

Nigerian Modernism will be on display at Tate Modern until 10 May next year, aiming to shine a light on a movement that has long been overlooked on the global stage.

"This exhibition comes with a message we can take home," says Onobrakpeya. "It gives us hope, it strengthens us, and we’re going to work harder to create something even greater than this."